In his post-General Conference briefings, my own Bishop Frank Beard urged us to trust in the process–not merely the United Methodist process, but God’s process with us on this discipleship journey, however long and winding and painful it may be. For him that means that we prayed for years for the work of General Conference 2019, so the fact that we might not like its outcome is not a good enough reason to summarily dismiss its conclusions and legislation. To put words in his mouth, “Did we pray or not? Does God answer prayer or not?”

I don’t dismiss General Conference 2019’s work. This was our 2019 step on our journey with God as a global United Methodist Church. It was neither our first nor our last step on our journey with God, even if some of us decide to part ways with this particular institutional form of God’s one Church.

The reason I write this is because you might get the wrong idea from my last post on the relative importance of General Conferences, that I am flippant about the conclusions of church councils. I’m not. Rather, the Christian Tradition itself is what teaches me to receive the Tradition itself critically. That’s how all living traditions work, as wide rivers with many currents rather than tiny capillaries with single currents.

I have known people who claim to aim to be “first five hundred year Christians” (meaning, the stuff the Church agreed about for the first 500 years is what they will name as essential doctrine, and everything that cannot be connected to that is adiaphora). I was once ordained in a denomination which claimed the first seven ecumenical councils were its theological core, but I’ve only ever met one person who I believe actually knows those councils intimately. (She died several years ago and was Roman Catholic, not this other denomination, anyway.) Either of those frameworks seem nice, but what they really are are “fragments [we] have shored against [our] ruin,” our sense that things are falling apart, and we are the ones who must save the Church. Those two examples in particular are entirely modernist attempts to create something stable and lasting in an uncertain world, which is in the end the attempt to create a foundation other than Christ (1 Cor. 3:10-11). (Alternate Old Testament reference: Genesis 11.)

I myself am temperamentally conservative. That is, I want to live a traditioned life. I am convinced that human beings over time have learned to live life well, to ask and to answer important questions well. I am convinced that to ignore those human voices of the past is the definition of foolishness. When I read a book about any topic at all, I want to go back and read the primary sources. When I listen to music, I want to plot where parts of a band’s or a composition’s sound comes from. And when I do theology I want to dig all the way to the tips of the roots. In fact, when doing theology, I am convinced that ignoring human beings and their thoughts and actions and lives over time is not just foolishness. This is truly for one part of the living, eternal body of Christ to say to another, “I have no need of you” (1 Cor. 12:21).

Conservative in the sense in which I describe myself does not have to do with a particular political party, especially not a US political party. Traditioned in this sense also doesn’t mean I pretend that there is some single Tradition to be formed by. That’s utopia (sentimental nonsense literally meaning “nowhere”). For my greatest interest–the Church–I don’t believe there is some single faithful Methodist, or Protestant, or Western Christian, or universal Christian tradition. Instead I mean that I am always going to be suspicious when a “new” theology seems to have no roots, or makes no claim to roots, or claims to need no roots in the Christian past. The Tradition may be a massive river with many currents, but rivers still have banks.

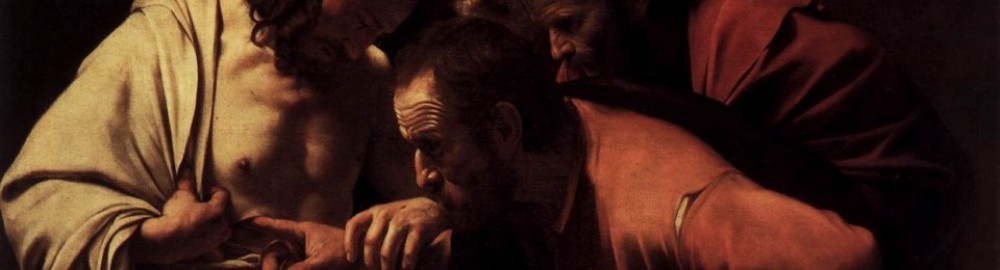

All that is a long-winded way to say, yes, I believe church councils have proclaimed the Gospel, but I still believe they have erred. Yes, I believe General Conferences have both proclaimed the Gospel and have erred. Finally, no, I don’t dismiss their workings easily. The Tradition I value is what teaches me to question the Tradition and to know it is certainly not infallible.

That’s the real point: the life of faith–whether for global denominations or for the individual Christian–must be lived in uncertainty (“the conviction of things not seen,” says Hebrews 11:1), because faith lives in the world, and the world is uncertain. Faith which is certainty is not faith at all. God keeps speaking through people (councils, conferences), people sometimes faithfully proclaim and sometimes mangle the message we’ve been given, and the Church’s life and our individual lives are lived in that uncertainty and on that journey. We live in our uncertainty, because God is the only one who is certain. We live without the foundations we lust after, because Christ is our one foundation. Thank God that God’s grip on us is infinitely stronger than our ability to grasp God.

Or if you prefer less Kierkegaard and more Wesley in your tea, the church has not yet been perfected in grace, but it is on the way. Even if you find yourself among those United Methodists who believe that in St. Louis you witnessed the death of your beloved denomination, still you must know: best of all, God is with us.

Pingback: Our Hope Was Never in General Conference, Part I | Mostly Consolation